The Best Way to Improve Your Edit

Okay, let’s get straight to the answer.

TLDR: Watch your cut with someone else beside you.

That’s basically it. They don’t even need a background in film or TV.

Yes, it has little to do with your NLE’s specific tools (though important), your timeline and bin organization (also important!), or your relentless drive to make your cut better (foundational). And yes, this is counting on the fact that you have already reached the assembly step or further.

But watching a cut with someone else, ie, a test audience, is unbelievably benefitial to an editor as it helps discern what’s working and what’s not.

(Subway) Map of the Story

I’ve been making my way through Oscar-winning editor Tom Cross’ masterclass (no, not that Masterclass). Cross is a obviously at the top of the game, having cut enormously successful films Whiplash, La La Land, and First Man. While the course is geared more towards students, I figured it could only help to see how someone as accomplished as Cross works at his craft.

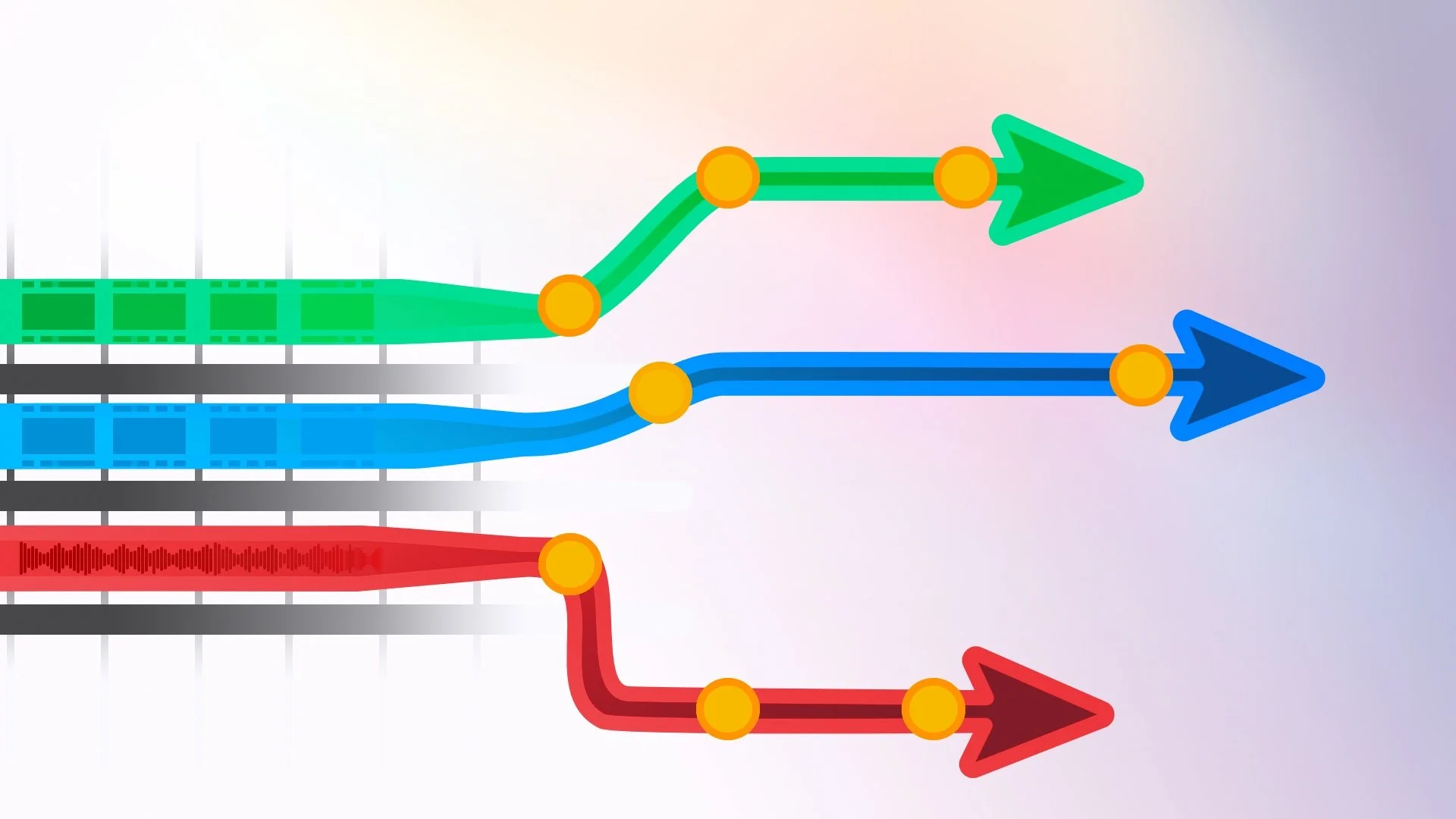

In an early lesson, he cleverly draws a parallel between film editing and the NY Subway system’s signage. Pre-1960s, the signage was a long string of streets and destinations, an absolute information dump. Useful information for sure, but a total visual overload:

Cross compares what happened when designer Massimo Vignelli was hired by the Transity Authority to completely remake their signage and mapping. Vignelli went much further. He spent years watching how commuters moved through the subway, when and where they looked up for information, and what decisions they made. With this real-world knowledge, he created a unified system that allowed commuters to parse and be given the information at the exact right time.

The signage at subway entrances were simplified to note which train lines were available. Once down the stairs, you’d find further information on whether to take a right or left on the the pathway to reach a smaller set of train lines. Finally, you’d make turn off for your specific train line, with information about a connection or landmark. The further you go through the path, the more detailed and specified the information would be.

Which is, of course, what editors are trying do with their cut. A well-edited story gives only the right information at the exact right time.

Story information being given too early or too late are equally problematic. As for what determines the the correct timing, that’s to be instructed by the edit and the film’s own intentions. Sometimes you may want the audience to be ‘ahead’ or ‘behind’ a certain character.

Case Study

For a simple example; in episode 2 of Slasher: Guilty Party (on Netflix @ 28m20s) I cut a scene where we find the characters Dawn and Peter in a cabin they have barricaded to keep a mysterious killer out. Dawn holds a gun in her sleep. She suddenly bolts up, hearing footsteps outside, and points the gun at the door. She’s frozen, watching the door behind a mountain of chairs. Close-up on the doorknob’s lock turning. A pause. The door jerks open, causing the furniture in front of it to come crashing down. Dawn freaks and fires the gun. Then we cut outside to see that is was only her friends Keira and Mark, who are now running for their lives.

At first, the scene was assembled to include coverage of Mark and Keira at the door earlier; the ‘reveal’ would occur before the door is unlocked and Dawn fired the gun. The idea was that we could first build up Dawn’s fear as we were building up the audience’s anticipation, and then twist the audience’s anxiety by leaping ‘ahead’ of Dawn’s POV. Showing Keria and Mark before the gun is fired, we built up a different worry in the audienc: will Dawn hurt her own friends?

Ultimately, we decided to streamline that bit of storytelling. It was simplified to only reveal Keira and Mark after Dawn fired. I think giving this information in this way accomplished two helpful things. One, by staying with Dawn, we better understand her growing fear and (somewhat) justify her actions. Secondly it builds up anxiety in the scene without immediately undercutting it, allowing a natural peak at the attempted door opening.

Read The Room

Alright, so stories need to deliver plot and character details in a timely fashion - not exactly a revolutionary idea. But I found this whole the subway wayfinding metaphor lent itself futher; it answers the question to why test audiences are needed.

After editors have done multiple rounds of cutting, maybe even a polish pass, we want to figure out where the edit is failing. That’s why tips that help get the editor to see the cut with ‘fresh eyes’ are helpful. These include suggestions like ‘watch the cut with no audio’ or ‘flip your entire sequence’ or one I just picked up from Joe Walker, editor on Dune, ‘watch the cut in black and white’.

By breaking the comfort we have naturally built up with our own edit, we are more likely to see the holes and rough spots. And once we’re done with that pass, we’ll send a quicktime off to the producer or a trusted friend.

Feedback helps. Criticism is great. The email of detailed notes make suggestions concrete. But sometimes it just isn’t quite enough. What you probably need is to have someone view it beside you (on live a video call).

To be frank - this is extremely common advice. Possibly the most common in the edit room. But I think Cross’ metaphor made the reason why this works click for me.

You’re not asking someone if they got to a destination with no issues (which of course they’ll want to say yes, for fear of looking dumb) - you’re actively watching them find it. Instead of meeting them at the end of a commute, you’re watching them search, read the signs, and choose their paths. You’re seeing where they misunderstood and had to back track.

That’s immediate feedback. Feedback the viewer didn’t have to process to give you, or worry about articulating correctly. Of course they ‘got’ to the destination. But was it as smooth a story ride as possible? You wouldn’t know without seeing them squirm in the chair, burst into laughter, or totally zoning out.

When you view your work with someone else, you’ll read every beat differently.

On a recent television project, a producer sent back a note requesting I add in an insert shot of a character holding an instrument. Because it was requested for a specific moment, I had to time an actor’s hand moving across it, so that the continuity of the previous wider shot matched. I added the shot in, and made sure they matched. I watched the ‘new’ revision atleast 20 times to make sure the flow was good.

Later that afternoon, the producer joins me to watch the recent changes. When we get to the instrument insert shot I realize, yes the continuity is good, but I’ve cut the shot way too short. It feels jarring.

The producer doesn’t even need to speak before I pause playback and extend the shot by another half second. Why couldn’t I see that in any of the 20 times I watched it solo?

-

Watching the cut with someone else beside you is watching the cut with fresh eyes.

At that point, you can more clearly make note of what’s working and what’s not, and take another stab at it.